Frozen pipes

Pipelines of our dreams and reality. Voyageurs up the Nile. Canada Spends in the news.

In the depths of a -30°C Manitoba winter, the Pimicikamak Cree Nation transitioned from a holiday celebration to a humanitarian catastrophe. What began as a multi-day power outage in late December 2025 quickly spiralled into a total collapse of the community’s essential infrastructure, leaving thousands of residents without heat or water. Chief David Monias described a “war zone” of structural damage: collapsed ceilings, buckled floors, and sewage backing up into living spaces. By the time power was restored, the damage was irreversible for nearly 1,300 homes.

The crisis triggered one of the largest mass evacuations in the province’s recent history. Roughly 4,000 people, more than half the population, were forced to flee to hotels in Winnipeg and Thompson. Chief Monias issued a desperate plea to the Canadian Armed Forces for logistical aid, warning of an impending public health crisis fueled by black mould and fire hazards from makeshift heating.

While federal and provincial officials have since toured the devastation, pledging emergency funds and technical support, the road to recovery is steep. The community is now in a race against time to recruit enough plumbers to repair specialized northern plumbing before the spring thaw brings further damage. This disaster has reignited a long-standing debate over the systemic neglect of Northern Manitoba’s infrastructure.

Related: How Calgary screwed up its water infrastructure, and how other Canadian cities are in the same boat.

A failure of imagination

For much of the Trudeau era, Canadian energy policy rested on a pair of propositions that were treated less as arguments than as settled facts. The first was that there was no compelling business case for exporting Canadian liquefied natural gas to Asia or Europe. The second was that any expansion of oil production (and therefore of pipeline capacity) would inevitably undermine Canada’s climate commitments, making an emissions cap on the oil sands not just prudent but morally necessary. Together, these ideas led to an enormous strategic complacency: Canada could afford to strand its resources inland because the future, we were told, did not require them.

Well the future has arrived, as it has a habit of doing. And what has changed is not the physics of climate change or the chemistry of hydrocarbons, but the geopolitical context in which Canadian energy is produced and sold. As Samuel Johnson once sort of observed, the prospect of being hanged concentrates the mind. Donald Trump’s threats toward Canada’s sovereignty — however volatile or performative — combined with his administration’s seizure of Venezuelan oil assets, have had a similar clarifying effect. They have forced Ottawa, and a broader swath of the Canadian policy class, to confront an uncomfortable reality: a country that cannot reliably get its resources to market is not just poorer than it needs to be, but more vulnerable than it can afford to be.

This is the backdrop to the renewed case for an Alberta-to-British Columbia pipeline. It is not an act of nostalgia for a fading third-tier petrostate, it is a strategic necessity in a world where energy security and political sovereignty are again closely linked. The question critics understandably ask is whether this urgency comes at the expense of the environment. Is Canada being asked to abandon its climate ambitions in favour of a brute, growth-at-any-cost nationalism, all out of a misplaced sense of geopolitical anxiety?

A new report from the Public Policy Forum suggests that this framing is too simple. Written by Mark Cameron and Arash Golshan, the central argument is not that Canadian oil and gas are clean in any absolute sense, but that where and how they are produced, and what they displace, matters enormously for global greenhouse gas emissions. If the goal of climate policy is to reduce emissions in the atmosphere rather than to signal domestic virtue, then the export of Canadian LNG and oil is almost certainly part of the solution.

The LNG case is the most straightforward. In Asia and parts of Europe, the marginal unit of electricity is still overwhelmingly generated by coal. Canadian LNG, even accounting for upstream production and liquefaction emissions, is significantly less carbon-intensive than coal when used for power generation. The PPF report concludes that Canadian LNG exports, if they displace coal rather than simply add to global gas supply, would lead to net global emissions reductions measured in the tens of millions of tonnes annually. This is not a speculative claim; it reflects observed substitution patterns in markets where LNG has already expanded.

The oil argument is more counterintuitive but no less important. Canadian oil sands production is emissions-intensive relative to conventional light oil, but global oil markets are not choosing between “oil” and “no oil.” They are choosing between different barrels. Heavy oil from Canada competes directly with heavy crude from jurisdictions such as Venezuela, which tends to have higher lifecycle emissions and far weaker environmental oversight. Similarly, Canadian conventional light oil often displaces supply from geopolitically unstable or environmentally opaque producers. In that context, constraining Canadian supply does not reduce demand; it reshuffles it in ways that can actually raise global emissions.

This is the kind of argument that makes environmental purists uncomfortable, because it rejects the idea that climate progress is primarily a matter of national self-denial. It also irritates parts of the Canadian left, which have grown accustomed to treating pipelines as symbols of moral failure rather than as vital pieces of national infrastructure. But discomfort is not an argument. If the PPF analysis is broadly correct, then a rigid focus on domestic production caps risks confusing accounting with global outcomes.

None of this means that a new pipeline is cost-free or politically easy. As Jen Gerson argued in The Line this week, Canada’s real problem may not be a lack of good arguments but a chronic inability to translate them into action. The regulatory gauntlet, the culture of permanent consultation, and the habit of treating every large project as a unity crisis remain firmly in place. A generic “pipeline to the coast” still has to pass through real communities and real ecosystems, and public consent cannot simply be waved into existence.

But the broader point stands. The old posture — that Canada could simultaneously constrain its energy sector, maintain its prosperity, and exercise meaningful sovereignty — was never anything more than a fever dream of the zero-interest-rate era. The shocks of recent months have exposed how reckless that position was. Growth and prosperity are not abstract economic preferences; they are the preconditions for political autonomy in a world where power is again being asserted bluntly.

The more surprising conclusion is that this need not entail abandoning environmental responsibility. If Canada can expand export capacity in a way that demonstrably lowers global emissions, then the supposed trade-off between climate and sovereignty looks less like a law of nature, and more like a a colossal failure of imagination.

Voyageurs up the Nile

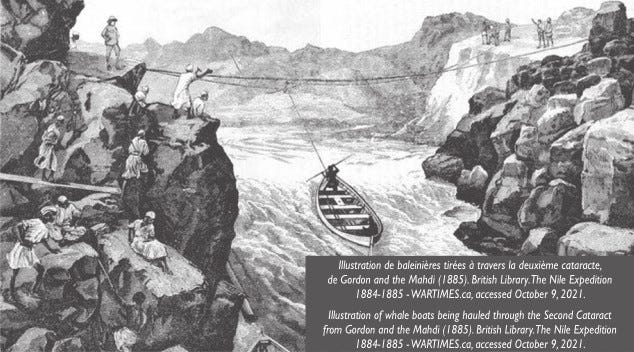

We thought we knew our Canadian history here at Build Canada, but we recently came across a remarkable episode that had escaped our notice. In the 1880s, approximately 400 skilled Canadian voyageurs were recruited by the British for the Gordon Relief Expedition to rescue General Gordon in Khartoum. The leader of the expedition was Sir Garnet Wolseley, who had served in Canada during the American Civil War and who had played a key role in defending Canada from the Fenian raids.

Wolseley knew that getting to Khartoum would require navigating difficult Nile cataracts, and for this he turned to the Canadians who had so impressed him. This was Canada's first significant overseas military mission, involving civilian boatmen famed for their river skills, with many coming from the Ottawa Valley. Another notable Canadian, Sir Percy Girouard, later built the desert railway that helped capture Khartoum in 1898, continuing Canada's involvement in the region.

This is not a widely known or celebrated story; the only comprehensive book on the subject is Canadians on the Nile, written by the former diplomat Roy McLaren and published in 1978. A companion of sorts is Mohawks on the Nile from 2009, which focuses on the sixty indigenous men who joined the Canadian Voyageur Contingent.

Chart of the Week

It cost the government ~$83B to settle indigenous legal claims from 2013-2025. Since the 1970s, the government has settled, remedied or has had to pay court-ordered compensation for 830 specific claims (out of 1205 concluded claims). There are 811 further claims in progress. More data can be found at Canada Spends, whose work was featured on the front page of the National Post this week.

What else we’ve been reading

Pierre Poilievre was on The Knowledge Project Podcast, with topics crowdsourced from the Build Canada community. As host Shane Parrish notes, “we are trying to improve political discourse by offering a platform for both sides to speak with depth and nuance.”

Kepler Communications is launching its first wave of orbital data centre satellites on Sunday, on a SpaceX rocket in California.

A year-opening roundup in the FP of the startups looking to fix Canada’s myriad problems included Wealthsimple, Cohere, Dominion Dynamics.

The men’s and women’s rosters for the Olympic ice hockey teams have been announced.

A French-UK consortium is pitching Canada on a sovereign alternative to Starlink for the Arctic.

Stephen Harper’s official prime ministerial portrait, by the Canadian artist Phil Richards, will be unveiled at a ceremony on Parliament Hill on February 3.

The Pentagon has asked a Toronto sex-toy shop to please stop sending butt plugs to its soldiers overseas.

Get weekly, no-fluff insights on building a more prosperous Canada. Tap “Subscribe” now and be first in line for next week’s brief. Then forward this email to one friend who cares as much as you do—let’s build together.

That $83B settlement figure points to a glaring trend in the Public Accounts. The "Contingent Liabilities" for Indigenous claims now often exceed the entire annual operating budget for Indigenous Services. We see this pattern in committee transcripts constantly. MPs debate the upfront cost of water infrastructure, the funding gets deferred, and the government eventually pays more in legal settlements than it would have cost to fix the pipes in the first place.

It's astonishing that commentators like the authors of the pipeline story have no energy industry background and can't produce a lick of data to support their argument. Your nonsense is grounded in nothing more than industry talking points. Go read some global energy demand modelling studies. If you have the courage, find some Chinese oil demand modelling studies. Then you'll understand why the argument for a second West Coast pipeline is completely bogus.

Alternatively, maybe understanding isn't what you're after...